Pakistan will face a critical review of its financing facilities at a crucial board meeting of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Washington on Friday, as it plans to seek funds for its cash-strapped and debt-ridden economy. India is going to oppose the additional funding to Pakistan at the Board meeting, having already made its stance clear.

Tensions between India and Pakistan have soared, raising concerns globally about the possibility of the nuclear-armed neighbours getting entangled in a prolonged conventional military conflagration. The fragile state of Pakistan’s economy, however, does not lend itself well to an extended military conflict.

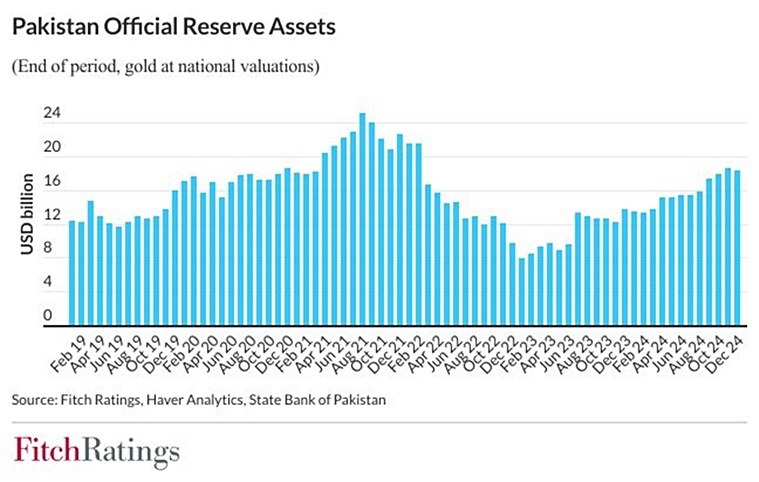

Pakistan is riddled with high foreign debt coupled with perilously low foreign exchange reserves, and has been grappling with an almost perennial balance of payment crisis and high inflation in recent years. Islamabad’s external debt jumped to over $130 billion in 2024, over a fifth of which was estimated to be owned by its key ally China. In contrast, Pakistan’s forex reserves are pegged at a little over $15 billion, capable of paying for just about three months of imports. Reserves remain low relative to funding needs, with over $22 billion of public external debt maturing in FY25, including nearly $13 billion in bilateral deposits, as per a Fitch report in February. In April, Fitch had then noted a pickup in Pakistan’s reserves accumulation.

IMF bailout

With elevated debt levels and low reserve buffers, Islamabad had earlier managed to get a bailout package from the IMF in September 2024 with the approval of a $7-billion loan, following which its economy has shown some early signs of a recovery from the brink of a collapse. As per the latest South Asia Development Update released in April by the IMF, Pakistan’s economy has been recovering from a combination of natural disasters, external pressures, and inflation. While inflation has slowed more quickly than expected along with strong imports of capital goods and high consumer confidence suggesting a pickup in private sector growth, the incoming data on economic activity have been weaker than expected, the IMF said. Economic growth of Pakistan is projected to rise to 3.1 per cent in the financial year 2025-26 from 2.7 per cent in the financial year 2024-25, 2.5 per cent in 2023-24 and a contraction of 0.2 per cent in 2022-23.

The ongoing 37-month long Extended Fund Facility programme of the IMF consists of six reviews over the span of the bailout, and the release of the next tranche of approximately $1 billion will be contingent upon the success of the performance review. The IMF board is meeting Friday to review the financing facilities extended to Pakistan, where it will face stiff opposition from India for diversion of funds towards terror financing in the backdrop of the Pahalgam terror attack on April 22.

The other multilateral bank, the World Bank, also expects Pakistan’s economic activity to pick up in FY26 (3.2 per cent) and FY27 (3.5 per cent). However, it has also flagged that Pakistan’s growth will likely remain constrained by tight macroeconomic policies focused on rebuilding fiscal and external buffers and mitigating risks to economic imbalances.

Story continues below this ad

Potential macroeconomic policy slippages — driven by pressures to ease policies — along with geopolitical shocks to commodity prices, tightening global financial conditions, or rising protectionism could undermine the “hard-won macroeconomic stability”, the IMF had pointed out in its statement in March this year after the first staff-level review of the loan facility extended to Pakistan.

Funding from other multilateral institutions like the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank is also crucial for Pakistan’s economic revival and securing it would be a challenge as India steps up its ante by seeking support from all MDBs.

When the bailout package was secured by Pakistan last year, the IMF in its report in October had assessed the overall risk of sovereign stress for the country as “high”, saying that it reflected “a high level of vulnerability from elevated debt and gross financing needs and low reserve buffers”.

“Notwithstanding the new government’s intent to deepen reforms under a new Fund-supported program, political uncertainty remains significant, and pressures for easing policies and providing tax concessions and subsidies are strong. A resurgence in political or social tensions could weigh on policy and reform implementation. Policy slippages, including particularly on needed revenue measures, together with lower external financing, could undermine the narrow path to debt sustainability, given the high level of gross financing needs, and place pressure on the exchange rate and on banks to finance the government,” the IMF report had said.

Story continues below this ad

In such a dire situation, a money-guzzling conflict with India should be the last thing on a beleaguered Islamabad’s mind, as it would have to essentially fund any long-drawn-out conflict with borrowed money. And while a prolonged military conflict with Pakistan is bound to impact India to some extent, the world’s fastest-growing major economy appears far more equipped to handle the economic impact in such a scenario. These crucial points have been underscored time and again by experts and analysts.

In fact, just two days before Operation Sindoor, Moody’s Ratings cautioned that “sustained escalation in tensions with India would likely weigh on Pakistan’s growth and hamper the government’s ongoing fiscal consolidation, setting back Pakistan’s progress in achieving macroeconomic stability”. The global ratings agency added that a persistent increase in tensions with India could also impair Pakistan’s access to external financing and pressure the country’s forex reserves, which remain “well below what is required to meet its external debt payment needs for the next few years”.

As for the impact on India, Moody’s said: “Comparatively, the macroeconomic conditions in India would be stable, bolstered by moderating but still high levels of growth amid strong public investment and healthy private consumption. In a scenario of sustained escalation in localized tensions, we do not expect major disruptions to India’s economic activity because it has minimal economic relations with Pakistan”. The ratings agency, however, added that higher defence spending in such an eventuality would potentially weigh on New Delhi’s fiscal strength and slow its fiscal consolidation.

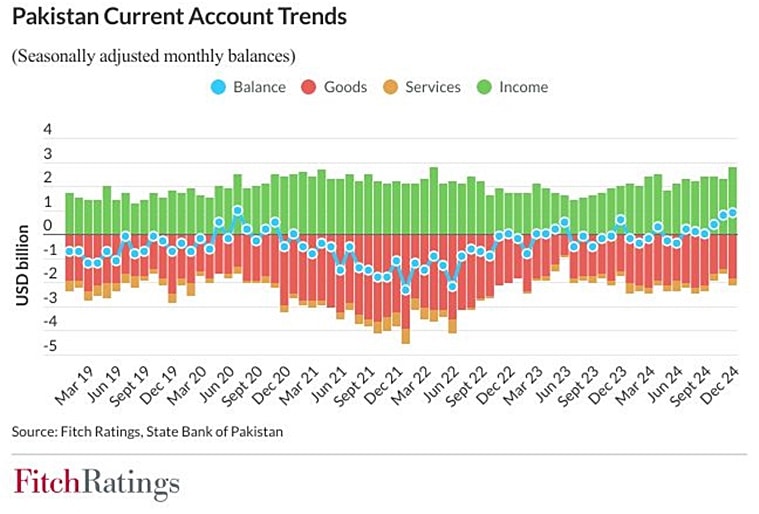

Experts and multilateral institutions have repeatedly flagged major structural problems and other risks plaguing the country’s economy that have largely remained unaddressed. These include high fiscal and current account deficits, political instability, low agriculture and industrial productivity, protectionist trade policies, heavy government interference in business, a large and inefficient public sector, a financially unsustainable and import-dependent energy sector, weak exports, and a small taxpayer base, among others. Natural calamities like widespread floods have also exacerbated Pakistan’s economic woes in recent years.

Story continues below this ad

Protracted hostility and conflict with India also poses significant risks for Pakistan’s labour-intensive agriculture sector, Yousuf Nazar, former head of Citigroup’s emerging markets investments, noted in his recent opinion piece in Financial Times.

“Pakistan’s real economy, particularly agriculture, would also suffer. India’s suspension of the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty sends a destabilising signal. Agriculture remains the backbone of Pakistan’s economy, employing nearly 40 per cent of its labour force. Combined with ongoing political instability and the lingering effects of the 2022 floods, the country is ill-prepared for another major shock. A single crisis could trigger economic collapse and mass suffering. For Islamabad, avoiding significant escalation could be a question of survival,” Nazar wrote in FT.

“Even if a full-scale war appears unlikely, the potential for limited hostilities — frequent in the fraught history of this rivalry — remains high. And short lived escalations can still impose outsize economic and human costs, particularly on a country as vulnerable as Pakistan,” Nazar wrote.

Energy constraints

While Pakistan has made some progress towards macroeconomic stabilisation, the economic hardships of the past few years have also led to a rise in poverty, as noted by the World Bank in its overview in March for the country. There are problems on the energy front too, with the country struggling with an electricity crisis and problems in imports of energy feedstock, which is essential for businesses to operate and household consumption.

Story continues below this ad

“Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the catastrophic 2022 floods and macroeconomic volatility, poverty has increased. The estimated lower-middle income poverty rate stood at 42.3 per cent for FY24 (2023-24) with an additional 2.6 million Pakistanis falling below the poverty line from the year before,” the World Bank said.

Among the key reasons behind Pakistan’s economic misery is the country’s import-driven energy policy, which has hit its forex reserves, stoked inflation, and forced it to borrow heavily, particularly at times of global energy price shocks. As noted in a March 2023 report by the Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce & Industry on the impact of IMF programmes on Pakistan, 15 of the 23 IMF programmes for Pakistan till then were sought by Islamabad during the various global oil crises over the years.

Moreover, with Pakistan’s domestic fossil fuel reserves depleting, reliance on energy imports has only been growing. The country primarily depends on West Asian countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates for crude oil imports, and on Qatar for natural gas. Pakistan is also a heavy importer of refined petroleum fuels, given the country’s limited domestic refining capacity. The country has also been grappling with smuggling of cheaper petroleum fuels from across the border in Iran, which takes a toll on the domestic oil and gas sector and hits Pakistani government revenue as well.

With a significant share of energy being generated in Pakistan using costly imported fuels, and with domestic inefficiencies, mismanagement, and high subsidies, the circular debt problem in the country’s power sector has intensified over the years, accentuating the country’s energy crisis. The IMF noted that an unreliable energy supply and high and unpredictable costs have negatively impacted economic activity and development in Pakistan, and the country’s energy sector has become a “major point of macro-fiscal risk as circular debt spiked over 2013-21 for power and 2020-23 for gas”.